Chimeric Icons: An Interview with Astrit Ismaili

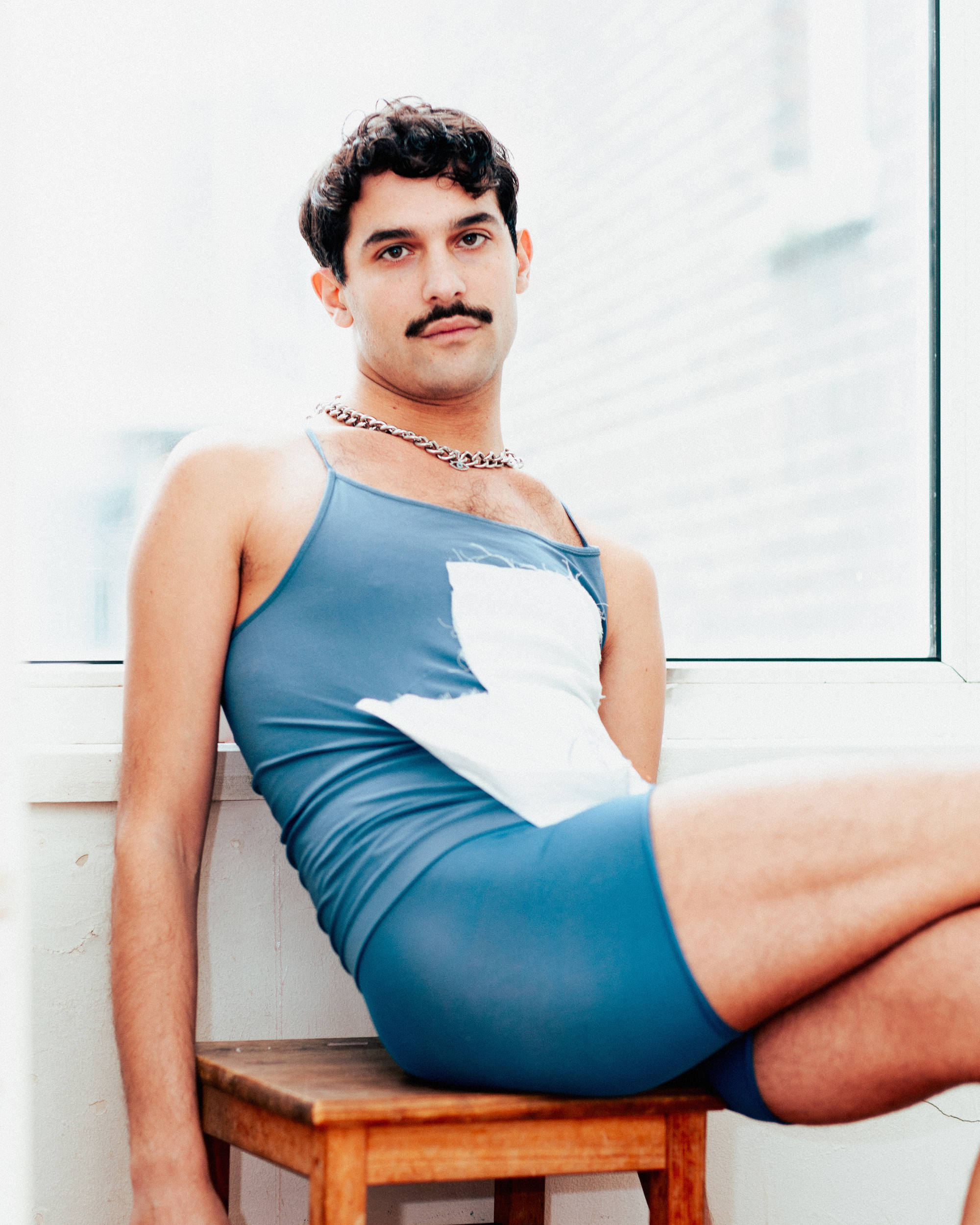

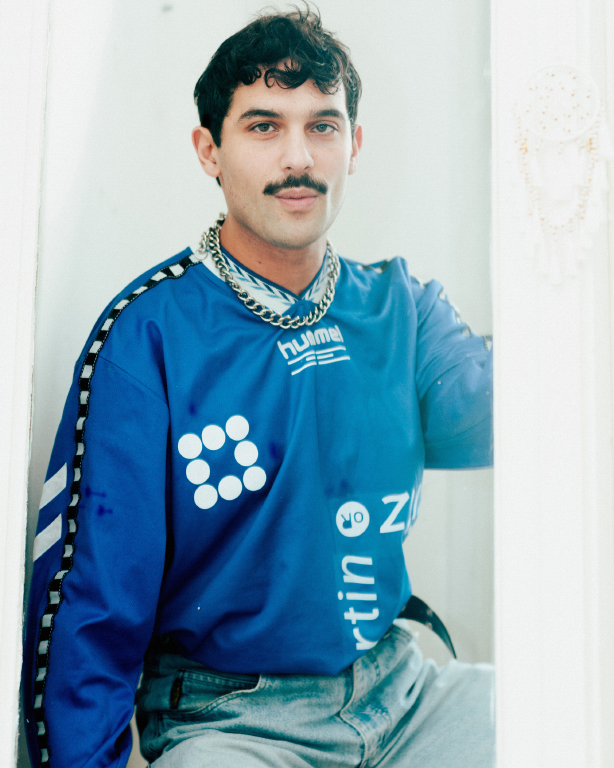

The interviews this past editorial year at Topical Cream have focused on giving advice to artists just starting out. How do we learn to experiment? How do we convey that we, as artists, writers, musicians, creatives, are always figuring it out, or in process of figuring it out? Some of the most interesting discussions I’ve read in the past few years are with artists in their eighties and nineties, who easily, frankly say, I am not sure, yet, what I do. I am still learning. To reaffirm a path toward the unknown, we have sought out artists and thinkers who can speak to their early and present models of experimentation. In December, I spoke with Astrit Ismaili about their rich imaginary and world-building around icons—as metaphor, as portal, as transformative beings—along with their stage activations, evolving experiences with their audiences, and the deep mythology that they build through their work. They were the perfect person to speak to about modeling a kind of experimentation, given the way they move from invention of avatars to performance, and the way they continually find subtle and overt ways to interrupt the presets of a space. Their fall performance at La Becque, where I met them, was exceptionally thrilling. Astrit came in with a serious challenge of the confines of performance in a formal setting, imbued with the preset expectations an audience might have of what performance in such a space should look like. Their works are staged activations, poetic and psychological and spiritual, based in precise technique. Eventually, the conversation moved into the practicalities of maintenance and how one sustains a practice, and invents, and reinvents, chimeric models, icons, for others to pick up and play with.

– Nora N. Khan, 2021 EIR

Nora Khan: Hi Astrit! How are you doing, and where are you right now?

Astrit Ismaili: I’m in my room now. These are going to be my last weeks in this apartment, because I’m moving out of here. I’ve been living here more than four years, but it’s time to move on. So it’s a period in which I try to not be so sentimental, especially when it comes to places, because I’ve been moving a lot in my life. If I was very sentimental, it would have been much harder for me to continue. I just see this as another chapter. As much as I’m trying to not be, I am a little bit nostalgic.

I met you only last fall here at La Becque, in La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, after the performance you did here. It was incredibly striking. You had what seemed like, from the outside, a very busy fall, full of a lot of work. You just followed it up with a performance at the Athens Biennale, titled Miss Kosovo. Could you maybe start to describe the Miss Kosovo performance, as an entry point into your practice, and as a moment where your creations of icons takes a concentrated form? You distill this decade of fictional figures and icons, which play on pop culture, self-commodification, and the vagaries and flux of gender identity, within the larger context of what it meant to take that space at Athens. What was that moment for you? What was the piece about?

Miss Kosovo is one of the references from another project called MISS, which is an hour-long performance. It is an opera for three performers in which I reference different historical and non-fictional subjects from the past, who had to be creative to overcome a certain type of limitation, whether that is a physical limitation or a geopolitical or environmental limitation. The whole research started when I was reading about the evolution of the first plant into flowering plants. I was not aware that plants, for many years, did not have flowers. Their reproductive processes were very difficult and not so sufficient. So in order for them to upgrade their sexual reproductive processes, they had to become very creative, and they came up with this structure, the flower. This is the shrinking of the stem, and the leaves on the stem become petals of the flower. This took thousands and thousands of years.

I found this moment of perseverance and resilience quite inspiring because then, metaphorically, I could connect this survival tool to many different stories, of many different people that inspire me. During this process, I was also introduced to the fact of Cicciolina’s existence by a friend of mine, Magdalena Mitterhofer, who’s also a performer. Magdalena was born in Italy. Every time we meet, we exchange epic pop culture moments. I’m very good at that for the Balkan region; I know quite a lot of iconic pop moments from the Balkans, and she knows a different kind of bubble. So we’re always exchanging and sharing these videos.

When I saw Cicciolina I was mesmerized by how she used her body in the public space, which was very uncommon and unusual in the ’80s and ’90s. She expressed her sexuality with a sense of the grotesque but also naïveté, which was very intelligent, especially when it came to the position of women in the ’80s. Cicciolina is quite complex. She’s kind of misunderstood because, on one hand, the feminists don’t really recognize her as a figure because of her use of her femininity and sexuality. On the other hand, the conservatives see her acts as blasphemy. I just find her path very unique and somehow never really understood. She transitioned from being a porn star to being a pop singer and then into the Italian parliament. Just as a trajectory, I think, it’s very compelling. I see her as a certain kind of flower, as well, of her kind, a certain type of first flower.

The third reference is Miss Kosovo, who is a fictional character. An actual “Miss Kosovo” doesn’t really exist. The figure is inspired by my experience of the Kosovo war, and of witnessing the construction of the Kosovo identity after the war. I watched how the state was being built, in all the possibilities, restrictions, and limitations. On top of that, while that was happening, I was being brought up as a queer person in an environment in which there was no discussion about gender issues. So the piece is very much about operating within environments in which there is no infrastructure, so the only way to survive is to build your own infrastructure and to be creative. I then came up with the notion, “Creativity when limited,” which has stuck around in my practice. From there, I take different references that relate to this idea of creating in limits. There are so many figures to commemorate, revive, and give a platform.

Performing in Athens was very special for me because Greece doesn’t recognize Kosovo as an independent state. Queer people are struggling a lot in Greece. I was very motivated; I had the honor to open the biennale with Miss Kosovo. There was a lot of Greek press and international press at the opening. Parts of the performance were broadcast on Greek national television during the news and a lot of media took pictures. It somehow burst the contemporary art scene bubble, and the discussion surpassed this context. Sometimes it feels like we are always showing work to audiences that don’t really need the discussion as much as the mainstream. This event constructed a bridge. I had a chance think about bubbles and directing the discussion where it needs to be.

“An actual “Miss Kosovo” doesn’t really exist. The figure is inspired by my experience of the Kosovo war, and of witnessing the construction of the Kosovo identity after the war. I watched how the state was being built, in all the possibilities, restrictions, and limitations. On top of that, while that was happening, I was being brought up as a queer person in an environment in which there was no discussion about gender issues. So the piece is very much about operating within environments in which there is no infrastructure, so the only way to survive is to build your own infrastructure and to be creative. ”

I was curious, watching the documentation of Pregnant Boy, and thinking about your early career as a child pop star. To move from that, to this exploration of loneliness and intergenerational sharing, channeled through pop. And your pop star figuration transformed, in your utterly singular story, moving from child pop stardom to your experience of war and dispossession. But you seemed to maintain this figure of the pop star throughout, and let it become hybrid. The figure begins to generate different models for, as you describe in your work, becoming and being. Could you describe early memories, formative moments where you can recall the feeling of experimentation as channeled through a pop form?

Well, the first thing that comes to mind is my mom playing piano. She is a music composer. As a child, my sister and I witnessed her composing music. So she would wake up in the middle of the night sometimes and just go by the piano to make melodies.

It’s pretty common in Kosovo to have a song or a few songs as a child. There are a lot of children’s festivals in Kosovo and even my relatives, when they were young, were singing. Since my mom was a composer, she composed songs for me and my sister, and so I was singing with my sister the first time we performed in 1996, if I’m not wrong.

So, you were five years old?

I was five years old, yes. At this children’s festival in Pristina. But this was during the ’90s where the political situation in Kosovo was really difficult and there was a lot of tension. Yugoslavia was falling apart. There was a war in Bosnia. We performed at this festival and after that year, the festival ended. This was our first and last performance during this period and then the war happened. It started in 1998, and it ended in 1999. And then in the early 2000s, in the first few years, me and my sister were still participating in children’s festivals here and there, but we were also going to school and doing what every other child was doing. When I asked my mom, “Why did you get us enrolled in this music career? What was your vision?” She said she believed that activities like art and music would be a nice way to cope with trauma. That was her strategy to kind of keep us busy. And I think it really helped because it was a beautiful time for me and my sister. It didn’t feel like work. It really felt like a fun thing to do to perform with other children.

I both identify with this, and adore and respect that your mom had the foresight and intuition to know that creativity would be the way to process massive trauma. But did you have any models then, for making music as a career or life path, that seemed achievable? Or was it more about the day-to-day play of music and enjoying it together as a family, with your siblings and your mother? Did you see in other pop stars something that you wanted for yourself or was it more just part of your daily environment?

When I became a teenager, I stopped singing, I wanted to disassociate myself from the child star image. With my friends—we were listening to all kinds of music. We were at first listening to black and death metal, and we became these goth kids. We had a collective, and called ourselves Evilmakers.

Amazing.

We would make short films and photos. They were very obscure, dark, lo-fi, and DIY. They were cute, but they were also dark as fuck. I realized that within the arts, there’s much more space for experimentation, because the pressure to make compromises for the industry is much smaller. You have much more freedom to express all kinds of visions. I started doing photography. I was very young.

“I started studying theater directing because I didn’t want to be an actor. I didn’t want to play roles that would be assigned to me. I wanted to create worlds and bodies that I had visions for.”

I was less interested in photography as a medium, and much more in what was happening in front of the camera. So I was curious about creating these characters, these alter egos, these figures and spaces, over capturing any one particular moment.

I started studying theater directing because I didn’t want to be an actor. I didn’t want to play roles that would be assigned to me. I wanted to create worlds and bodies that I had visions for. But this was definitely not what I would have studied, if there were options, for example, to study performance, performance art, or something close to that. But there were no options really. So I had to pick that one and be creative with that one.

It sounds like a way to have invented a practice or invented a path for yourself, which is the frame of what we’re talking about this year. How do you invent a path for yourself when no one has done what you’re doing before? You moved from refusing the role of an actor, and being solely interested in pop, to instead being drawn to construction. How do I create the scene? What is happening in this space before the camera? I love how you described this: what was happening in front of the camera was far more interesting than just being a person in front of the camera. It sounds like you were starting to actively invent a way of practice, perspective, and inversion of perspective, that your practice now is rooted in. Does that seem fair?

Yes. For sure. That’s how it was. While I was studying, I had to stage all the classical plays, including Shakespeare. I had this resistance. I just found it (back then) very pointless to still stage plays that were written such a long time ago. I would take those texts and really cut the shit out of them. I was very violent with the texts that were given by my professor, and it kind of worked out because then my performances were always really different from everybody else’s.

This moment of actively ripping the canon, literally ripping the canon up.

Literally. I would get a piece of text and I would just maybe take three sentences from it.

In your work, there’s a lot of very oblique references to mythology and slanted references to iconic figures. But without the weight of the canon. That’s why it feels so new. They still keep the air of archetypes that people resonate with psychologically. And I suppose we are psychologically trained through culture to need or be drawn to archetypes, which long have represented elements of our psyche in plays and in theater.

It sounds like this ripping of the canon allowed you to strip things down to just what you needed. To reply to the current moment and what people needed to see. Or what you needed to see.

Yes, that’s true. But also this resistance was not based on the content of the material. It was more based on this pressure that I would become another product of the institution. I didn’t want to become what the institution was producing. So I didn’t trust the material, but looking back, I wish I actually had dived in and studied it more, but I had this resistance. I was thinking, “This is bullshit.” But now, later on, references in my work became a way to expand it beyond the personal. And it is also of importance for me to connect to other narratives, which are similar to mine, or speak to me, or inspire me. That aren’t necessarily my lived experiences.

“I’m interested in the possibilities of becoming and the transformational potential of bodies. And therefore, the more open the spectrum is, the more possibilities there are.”

So this was a way for me to grow and open up the spectrum of possibilities. I’m interested in the possibilities of becoming and the transformational potential of bodies. And therefore, the more open the spectrum is, the more possibilities there are.

I’d love to talk about that opening up, of both the space with the audience, the stage space, and thinking about the staged activations of your practice. This compositional practice in which you’re mixing many styles. We spoke of your live avatar performances. There’s so many collaborators you have across the spectrum. You use sound as your instrument, you use your body as an instrument.

I keep coming back to the La Becque performance. This performance in relation to the unknown, and the unknown of a stage space, of a room. Not quite knowing what might happen. I’m wondering how you think of the spaces that you enter to perform in, and the preset defaults of them, how they’re designed. Before you begin a work, what kind of mental space and physical space are you thinking of?

This also kind of goes back to my theater directing studies. Given all the performances that we needed to stage on top of the lack of theater spaces, my professor always proposed we choose a site-specific space. So we would perform in a corridor of a building, or in a garden. And we were also pretty free to pick a location ourselves. And this was something I really loved, because it introduced me to activation of spaces through performance. It also made me realize that actually, the body is the most … the body has it all. For performance practice, I think that my investment mostly goes into the body itself.

The body is used as a tool to energize the space, and also to convey different narratives for voice and becomings, allowing the audience to witness these becomings. So then in my practice, usually I perform in spaces which are bare or have an identity, where that space has a function. And then I’m always finding ways to engage with that existing space. So I don’t have a scenography and I don’t have any set design. But when I have, it’s usually an empty space. So there’s nothing.

Have there been moments that were real challenges, where it was not possible to choreograph in the space, or aspects made choreography quite difficult? What were some challenges that you remember that come to mind that were formative?

Challenges? Acoustics. When you are singing, especially if you are using a bare voice and sometimes not even amplification, the acoustics can be a big problem. And this is a recurring problem that happens very often, because sometimes the spaces are not equipped, and the acoustics are not ideal for the performance. Performing in galleries, which I do, can be challenging.

Do you find that once you start to perform, that you attune to the audience, to how the audience is reacting? I’m thinking of a lot of performers speaking of the unknown of the space around the stage, and how their sonic composition or their acoustic composition then starts to change the space. It changes how people start to move toward the performer. It changes their attention. Obviously, everyone is focused. But then you had this incredible power at the La Becque performance. The sound was made to feel like it was moving backward. You were moving the audience, physically, semantically, emotionally through sound. You also changed, as we talked then, how we felt about the space we were in, the possibility of it.

I’m curious about the sonic landscape that you are creating and how that changes the audience, and how you imagine the audience changed and tethered and tied to the sound that you’re creating. How do you imagine you’re pulling and moving them through space with you?

I want to touch the audience through sound, and consider the voice a key element in my practice. I want to extract the vulnerability of it. And since the voice is produced from within, it’s already very vulnerable, but it also penetrates the other in an invisible way. It has a physical effect. I find that very powerful, especially through melody. Text is vital to my practice, as well, but it’s always somehow embedded in the melody and the compositions that I create. And I think the emotionality of the voice, and also, my trying to stick to a certain limited melody, which is a kind of a limitation, creates a powerful tension with the audience.

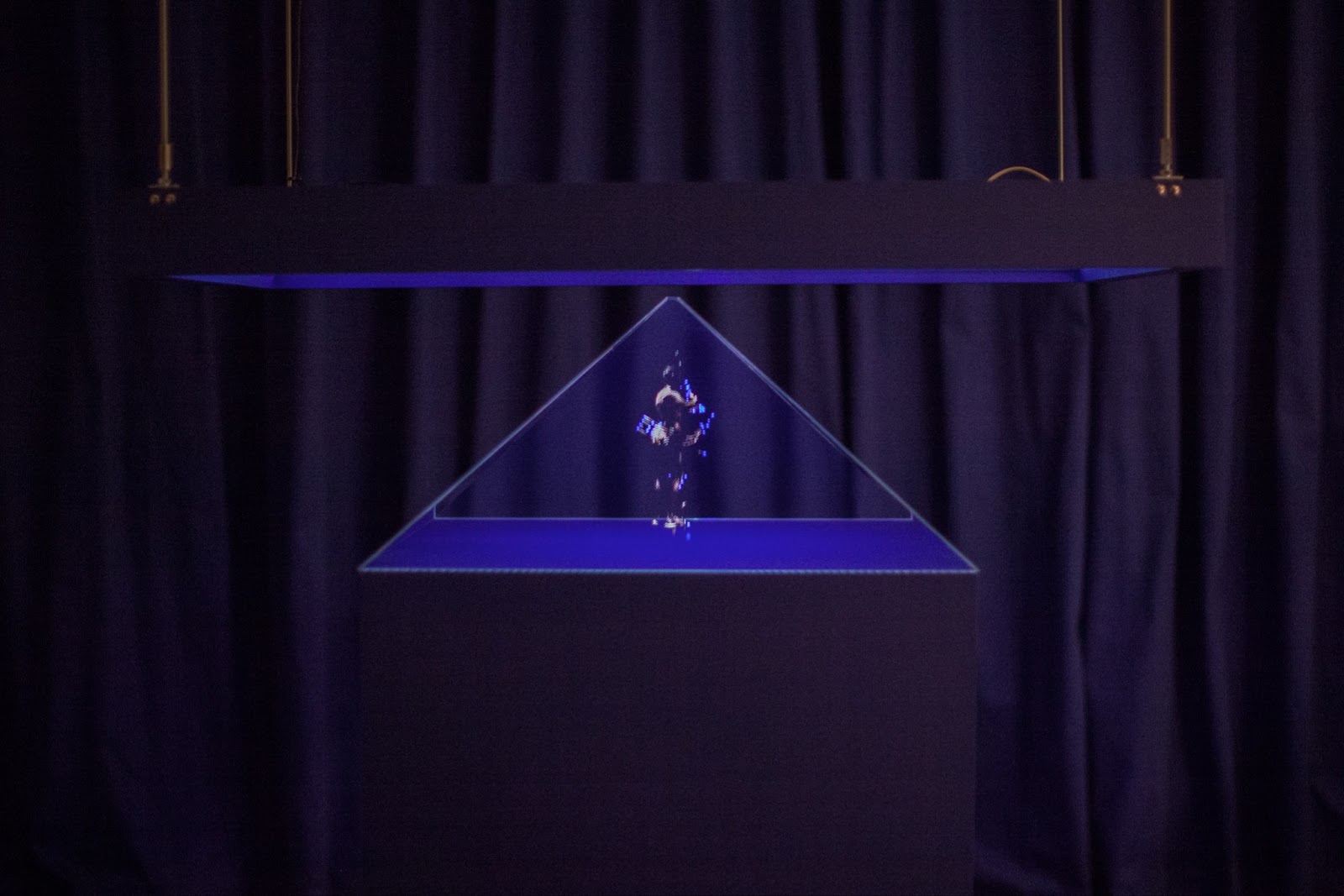

And then there are the wearable musical instruments. I have this performance, The New Body, in which I designed and wear the musical instrument, which has seven different parts. The hat piece, the hands, the hips, and the feet. And every time, the movement of the body is read by sensors and each movement of the body produces sound and the sound comes from the speakers, which are located on the instrument. So: the whole gives you the impression that the sound is coming out of the body. It would have been a very different experience in the space if I would produce the sound; the sound would then come from speakers who would be located in different parts of the space. I instead wanted to create an experience in which the body itself is really producing the sound — although the sound is digital, and these instruments are kind of extensions of the body.

“I want to touch the audience through sound, and consider the voice a key element in my practice. I want to extract the vulnerability of it. And since the voice is produced from within, it’s already very vulnerable, but it also penetrates the other in an invisible way. It has a physical effect. I find that very powerful, especially through melody.”

The new instrument that you saw at La Becque, with a string: it works with speakers that are located in different spots of the performing space. But because of the nature of the instrument, which is a string that gets pulled, which gets really long, it then has this architectural quality. The string changes the landscape of the space. And the sound also has a history, which you can see through this line, and through the trajectory of my movement in space. So it adds to the space in an architectural sense as well, and the sound is somehow the present moment of the movement of this line.

“The string changes the landscape of the space. And the sound also has a history, which you can see through this line, and through the trajectory of my movement in space.”

This way people can then visualize sound unfolding and moving, sound having a physicality as something moving forward in time and backward in time.

I’m curious about the moments after performances. You perform all over the world, you perform in wildly different cultural contexts. I’m curious about when you do sonic activation that is bodily: what kinds of responses and ideas do you hear across cultural contexts? Has it been interesting for you, to maybe feel that the piece is working or is effective in different spaces in ways that you didn’t predict?

Yes, because every time is different. The reactions are very different, because my work is, again, quite personal, and the lyrical content of my work tends to touch people in a certain way. There are lyrics of one of the songs that I perform, “The First Flower,” which go, “Life is really short, and I want the best of it. Life is really short, so be part of it. I have been so down. I had no reason to stay, but I found a way, and I am going to stay.” The lyrics are about this moment when the plant decides to become a flower, and how the only solution there, is transformation, but people connect to this idea in a very ambiguous way.

There was an audience member at Athens who came to me after the show. She said that she’s struggling with cancer at the moment, and that she felt both very moved and uplifted by the performance. It gave her motivation, and this was so touching to me. It was beautiful to hear that the content of my work can affect someone in that way.

Lovely. This comes back to something you were describing before in our last conversation, this tension between the deeply personal and having access to the universal. When I think of pop, I think of the universal. The idea of universal emotions is debatable and there are lots of theories about whether there is such a thing as a universal emotion or universal experience. The way that the lyrics you just described, and pop lyrics in general distill deep, personal pain, trials, and tribulations into something others can feel lighter in, regardless of context. Even if the work is deeply personal to you, others can react because they’re refracting it, applying it to their own life. Through your attenuation of sound and how you set up the space, there is a break, a point of access and entry.

Absolutely. Despite all the problems within the pop industry and the compromises that pop artists need to make in order to gain attention, all connected to financial profit and advertisement, I still find pop music also a generous act. It craves to connect to the mainstream through its form and its accessibility. It surpasses borders and it makes trends.

While I was growing up, there were so many pop stars and pop acts that really had a direct or indirect impact in my life and the life of my generation, if I can generalize. These moments and these figures are very important for contemporary culture, even if dismissed. They represent different voices and different eras through the aesthetics of their sound and their visual representation. I’m invested in pop culture as a phenomenon and I want to understand how it affects culture, and serves as a form of connecting with others.

“I am more intrigued exploring these possibilities of becoming, rather than presenting an icon who is un-compromised or perfectly defined. I’m much more stimulated by showing the possibility that such a transformation sits right in front of us. By embodying these figures, I comment on the institutional structures which control bodies by imposing roles that limit their transformational potential. ”

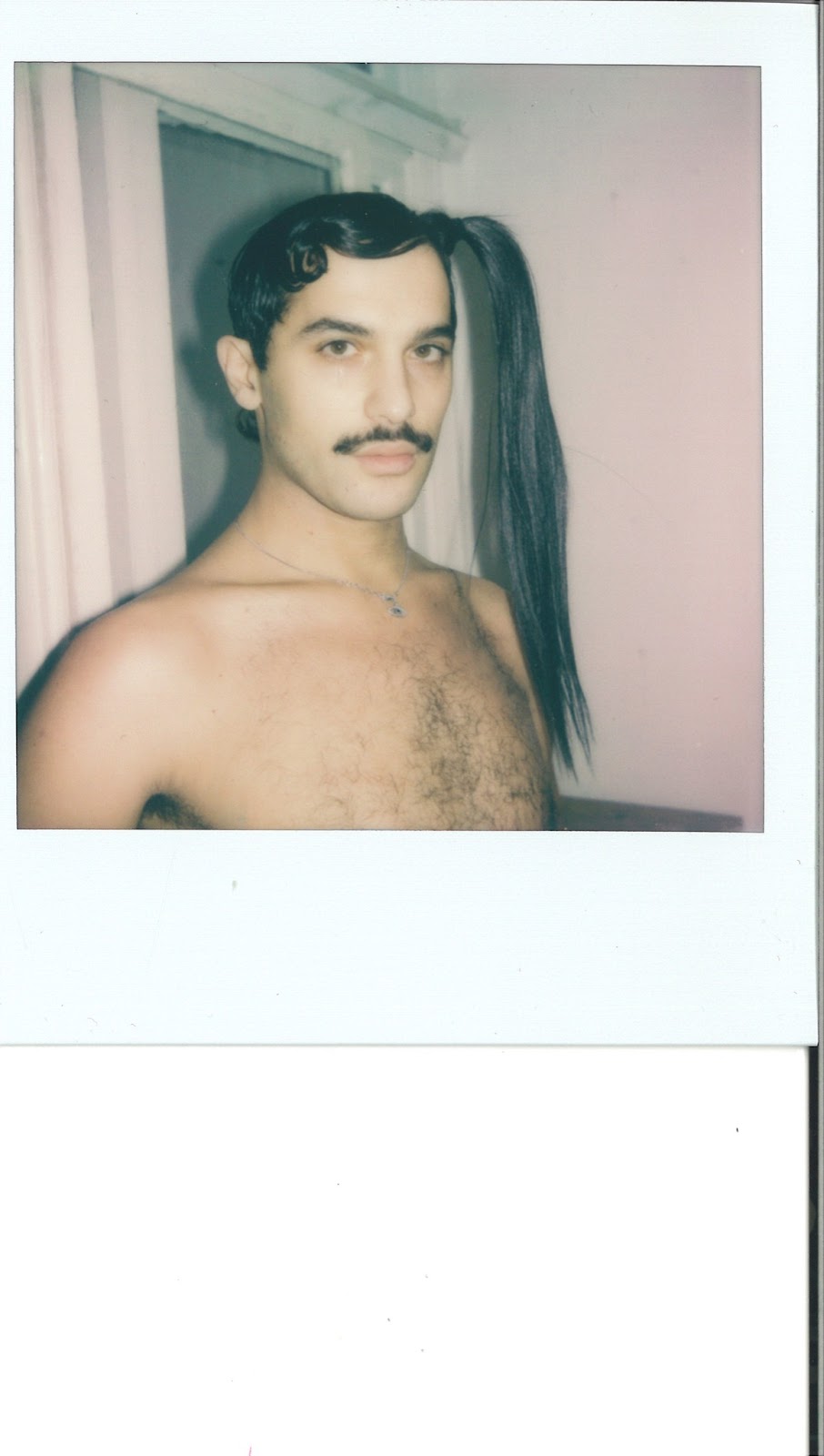

I wanted to turn here to some discussion of models and icons. So you have The Seahorse, you have The Pregnant Boy, you have Miss, and you have all of the iterations of Miss. They form a pop iconic mythology of your own, an iconic world of figures you’re assembling, each with their own narratives, brilliant stories, which are laden with history, which are laden with context, and full of complication. They’re not easy! They’re very difficult and complex figures, just like Cicciolina.

Maybe we can start to close by looking at these transitions between these iconic states and the icons that you’re choosing to develop. How do you see these icons as part of an iteration or refusal of the canon? Are they inversions or critiques, your world of icons, symbols, and associated myths?

In my practice, these figures often derive from the personal, but fiction is such an important part of their construction. Using speculative fabulation as a storytelling technique, I aim at blurring the line between fiction and reality but also what is natural and artificial. The multiplicity of these icons shows that one can embody many different states of being, and it can take so many different shapes.

I am far more intrigued by exploring these possibilities of becoming, rather than presenting an icon who is uncompromised or perfectly defined. I’m much more stimulated by showing the possibility that such a transformation sits right in front of us. By embodying these figures, I comment on the institutional structures which control bodies by imposing roles that limit their transformational potential.

We could talk about icons as a practice of futuring or a practice of imagining alternate lives for oneself. Pop stars create a fictional world in which we can imagine something beyond. They model shifting a paradigm beyond the current moment. And practice a kind of futurity in their world-building. But the challenge is important.

We’ve talked about the ways that neoliberalism in the digital sphere freezes us, has a way of pinning one to one’s identity as though these are one-to-one relationships. The capacity for change is lost. The idea of icons that model changing and constantly moving.

The icon as a chameleon or constantly shapeshifting or constantly reinventing one’s self. That’s the iconic representation of a shifting paradigm or relationship to the self. We can see that in your figures. A radical ideation of what an icon is.

These modes of queerness and queering have been present with me since before I even knew the terminology. Of course, queer theory derives from queer movements and activism. But queerness as a phenomena, is ancient, it is a quality in nature. There are endless examples from the botanic world of queer lives, which operate without any restriction, while in the human context, the political existence of queer folks is still not recognized. And I guess it has to do more with pushing these institutional structures, which categorize our bodies by restricting them from growing outside of these frames.

This ancient practice of constant reinvention. I was just talking to Colin Self about ancient queer cults and witchcraft as queer praxis. Or how “witchcraft” is used to describe a lot of kinds of queer practice, where anything outside of a dominant, hetero-patriarchal capitalist ya-dee-da space is in fact a constant practice of survival. In trying to function in all of these incredibly restricted spaces, like technology or art, or literary spaces or criticism, experimental practice is a way to live.

How would you say one invents an experimental practice? One’s always been practicing it, just by living day-to-day. That is the practice. Would you say, you’ve been working as an artist for ten years?

Yeah. Officially, about ten years, let’s say.

Wait—but really, it’s since age five, so, your twenty-five-year practice.

Oh, my God.

“… Queerness as a phenomena, is ancient, it is a quality in nature. There are endless examples from the botanic world of queer lives, which operate without any restriction, while in the human context, the political existence of queer folks is still not recognized. And I guess it has to do more with pushing these institutional structures, which categorize our bodies by restricting them from growing outside of these frames. ”

To close, maybe, could you please offer some reflection on how you’ve maintained a practice over time? How did you find ways to maintain and keep it all going, yes, but also maintain experimentation and experimental thinking over time? It becomes harder with time. There aren’t a ton of models of how to be an artist and performer and musician and thinker that’s reinventing themselves constantly, this practice of mutation and growth over time. What do you see as maintenance from day-to-day?

I was always kind of incapable of doing anything else other than my art practice. I tried. It didn’t work. I realized I just have to really not stop and devote all my time to my art practice, even in times in which it felt like a losing game. I didn’t stop. And then, persisting, devoting all my time to my art practice: this created a foundation that attracted interest from the outside world. I was always collaborating with different people, and stayed open to presenting my work in different contexts. But I don’t really have a model. I’m still figuring it out, but I guess not stopping is my advice.

How do you see your practice extending over time over the coming years, five years, ten years, twenty years?

My practice is mostly focusing on the body, and the lived aspect of it, the lived performance. But in recent years, I am thinking about ways to extend this practice beyond the temporality of a live performance. And I’m interested in creating spaces in which you can have access to the content of work when the performance is not active. So the audience can have a performative experience, with the space, using sound, and different objects, and drawings, as well. I’m currently working on a new music album, a publication of my drawings, and a film. I’m working with the same content, but trying to find forms in which the audience can have access after the end of the performance.

I feel it’s very exclusive to witness a performance. It’s a period where a lot of content is only contained, in the end, as video documentation, which is not really the work. I’m trying to find ways to create access for the public to the content of the work, because at the end of the day, I don’t do it for the form. I do it for the content. That’s what I want to talk about. Not so much about the form, more about the topics that my work brings.

“I don’t see performances as some kind of a new form just in the context of contemporary art, but in terms of an act of a body. We have always been performing rituals, ceremonies, and playing different games, and that’s what performance does as well. It proposes new games and new ways for how to be with your body, and with each other in this space.”

And then there are the games that you include in performances as they activate a space. You have the body balance dance, the knife game, the tray songs. They are so culturally rooted, and they’re very historically rich, and pull people in. I went down hundreds of rabbit holes looking at the knife game. Are you thinking of games as a method to bring people in these kinds of precisely choreographed spaces?

There’s so much performance embedded in different cultures, acts which aren’t really seen as performance. In every culture there are moments in which such performative stagings, events, happen. To bring them in the performance context, and bring them on stage is a way of proving that performances are really embedded in our everyday life, and performative elements of our everyday life. I’m not talking in the terms of Judith Butler, but more specifically about the rituals and performances that are actually as ancient as any other culture.

I don’t see performances as some kind of a new form just in the context of contemporary art, but in terms of an act of a body. We have always been performing rituals, ceremonies, and playing different games, and that’s what performance does as well. It proposes new games and new ways for how to be with your body, and with each other in this space.

That’s beautiful. The ways that we’ve invented artifice from the beginning. The cave paintings. We’re performing all the time, and all of life is performance and game play, and mediating constantly.

That’s why I find performance spaces are a rare platform in which you can explore these possibilities.

There aren’t a lot of other professions where you can experiment with space and the body. And I think this is such an important platform that we have, and it gives me this responsibility to use this space to bring to the forefront urgent voices and narratives that I feel are underrepresented in contemporary art.