Reba Maybury’s Art Subverts the Patriarchy by Making Men Work for Her

When I met Reba Maybury at a friend’s house in Glasgow, I was transfixed for hours, first by her Gaultier collection, and next by her insightful articulation of the male ego as discovered by way of masochistic rituals. Reba works as a dominatrix in London, but besides that, her credentials are intimidating, especially for someone in her twenties: She’s an author, a gallery-represented artist, the founder of a small press called Wet Satin, a radio show founder and host, a teacher at Central Saint Martins’ graduate program, and the list continues. She is incredibly open, admitting to finding her way through so many fields accidentally as she becomes interested in new ideas. She has been featured in periodicals as a contributing editor, a designer’s muse, and a subject whose thoughts on socialism and gender equality have sparked controversy. After a recent piece published in The Guardian on “the pleasure revolution” profiled her, the incendiary news site The Daily Mail lifted parts of the text and published an image-laden article called “Political dominatrix who uses mind games to humiliate her submissives reveals how she focuses her unique skills on white, right-wing men in order to turn them into socialists.”

Natasha Stagg: The Guardian article groups you with women who are mostly doing sex-positive art projects connected to self-discovery and female pleasure zones. Would you describe your work as different from that?

Reba Maybury: In a more perverse way, when I was first making men make my artwork (through my role as a dominatrix), for me, it was about female pleasure. I have always been incredibly aware that I’ve never been able to relate to pink feminism. Life for women is never going to get better unless men learn how to find different ideas of femininity attractive, or more precisely less threatening. By going to the root of their desire and analyzing it I am attempting to build something else up. The role of the dominatrix adheres to a socially unacceptable role that can only exist within the realm of underground pleasure. Her power isn’t supposed to be used for real choice-making outside of the fantasy. I want to instead push the boundaries and abilities that my fictitious role of powerful female can access.

Something I appreciate about your work is that you’re actually looking at the diversity of male sexuality.

Male sexuality is so powerful. It infiltrates so much. But it’s sort of taboo to give it too much credit now. It’s taboo to make masculinity look significant, and that’s what I do.

Can you describe how these ideas play out in your artwork?

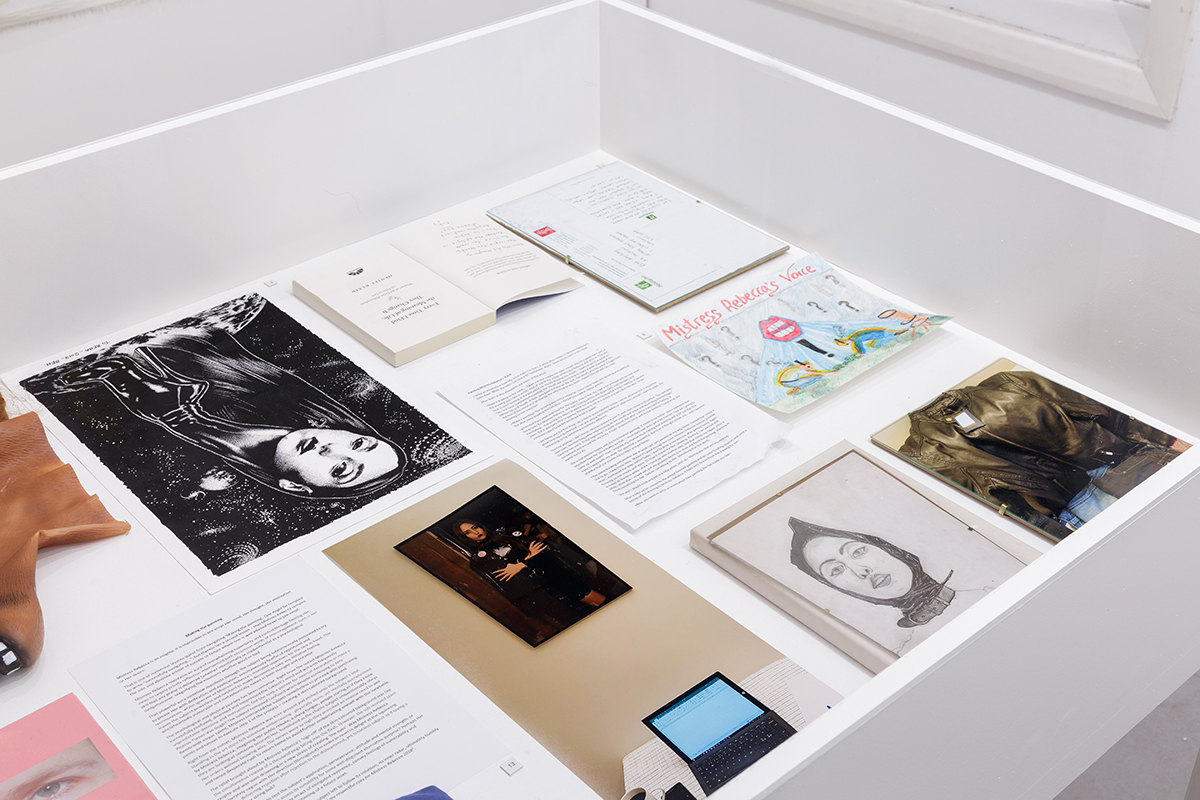

In my artwork, I want to remove anything that could be considered stereotypically feminine. I choose to work with the materials traditionally associated with men. Not just obviously male materials, like steel and oil paint, but their actual clothes, their actual drawings, gifts they’ve given me. I focused on this in Precious Expressions (2018) which was a vitrine filled with offerings from submissives. At first glance, they are all terribly mundane symbols of modern caucasian corporate masculinity, but by placing them in a vitrine they became worthy of being analyzed. There were pieces from these men’s work lives, the shoes they wear to the office, but then there is also the sexy secretary outfit from Ann Summers, which one liked to wear when he got home and would call me. I am fascinated by the eroticization of labor and power. They are my winnings much like the stolen objects filled in every Western country’s ethnographic museum departments, which are also prized within the midst of vitrines. These transactions and results are both hilarious and fascinating to me.

“When I was first making men make my artwork (through my role as a dominatrix), for me, it was about female pleasure.”

How do approach ideas of capitalism and elitism in these pieces?

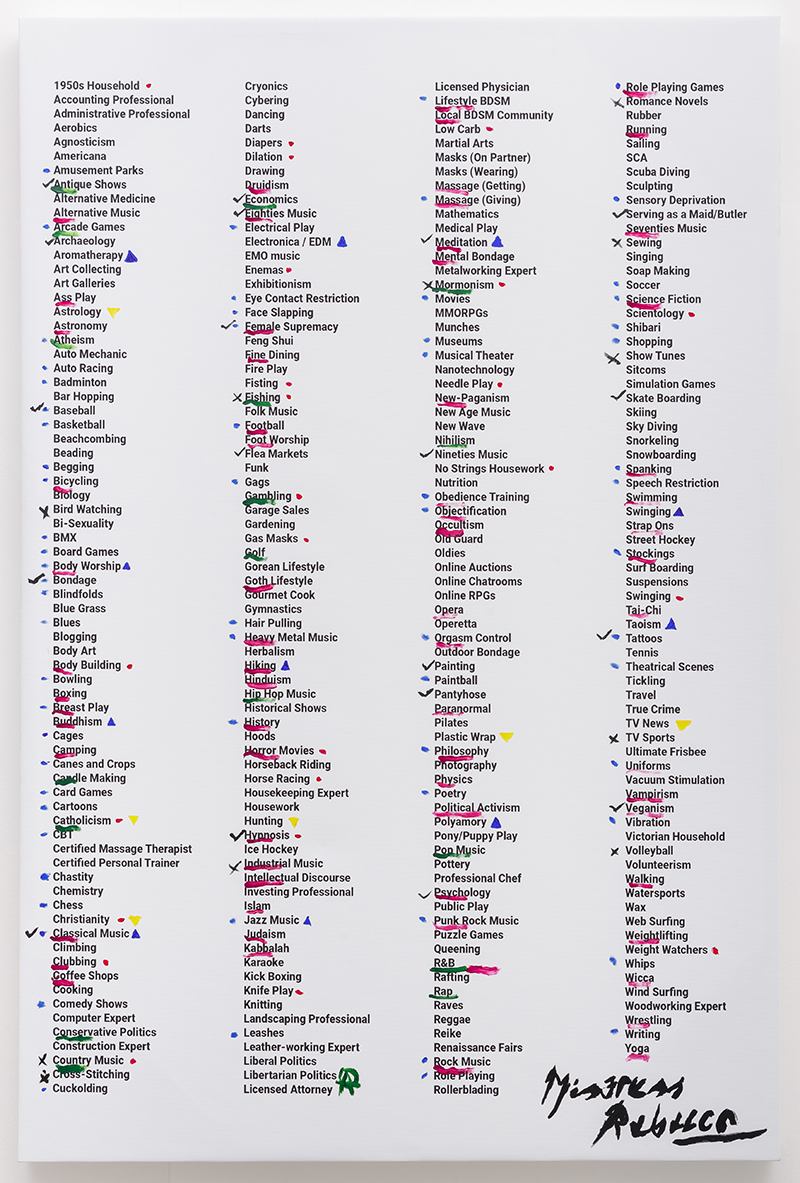

In my piece Fun (2018), which was on show at NADA, I explored the banality of ideas of leisure and enjoyment under modern capitalist society and how sexual pleasure interacts with this. I think a lot about what constitutes the idea of fun and what is acceptable. The canvas lists roughly four hundred activities that you can choose to either “like” or “dislike” on a fetish website I use, to add to your profile. The list ranges from the banal to the extreme, ass play to astronomy, chastity to chess, fishing to fisting, sensory deprivation to seventies music, and so on. The canvas is white and the graphic design layout of the activities was completed by a submissive.

Who filled it out?

I did sessions with four different submissives in November in an Airbnb in Soho. Upon their arrival, I gave each one a code for their likes and dislikes, which they had to paint onto the canvas. The result is an instantly sterile yet simultaneously childish painting that looks like a checklist or corporate document. Sex is often about play, and this is what this piece looks like. It performs the look of corporate male objectivity for something totally subjective, as well as parading the style of life administration or documentation-as-control. It acted as a way of knowing each man’s limits and perhaps a little about their personality while keeping them anonymous. There is also the factor that what these men may be saying they like or dislike—these are such superficial words anyway—they are only saying to impress me. Humor is of intrinsic importance to me and this piece makes me laugh. I signed my name at the bottom in the style of Picasso’s signature, cementing myself as the female artist, the person who labored, and an icon, which I am to these men. The work enables the viewer to partake in the humiliation but never truly understand these men’s sexualities. Instead, they are partially viewing the practice of my domination.

The idea of manipulation has a negative connotation, but it seems like you could empower through manipulation. If you’re getting submissives to turn into socialists, for example, that seems potentially empowering.

Even something as simple as making lifestyle changes can be empowering. I was having this conversation with someone the other day about the word empathy. We think of empathy as intrinsically positive. To be empathetic is good. It’s a very socialist idea, caring about others and being emotionally in tune. In reality, though, an empathetic person can be terrible, too, everyone can. Manipulation is a gendered word, but empathy as a tool to manipulate, perhaps it can be instrumentalized towards change.

The art world is supposed to be representative of the deepest feelings of our lowest class, but it’s absolutely impossible for that to happen when it is governed by the one percent. It’s a contradiction that’s existed for as long as the art market has. I think your art brings that contradiction into focus.

That’s totally accidental. The idea of making men do the work for me was directly about a power shift, a power play. If these men have more power and control in life than I do, I’m going to make them make something for me which will exaggerate my potential for power. It is a popular fetish for a man to want to do domestic work for a woman. They find it humiliating because it is deemed female. I thought more about what the possibilities of other types of labor that they could do for me were. We all know about gender pay gaps or gendered inequality in every sector, but I want to take that further by analyzing how far my own labor goes, from an initial message online to the end product, a piece of artwork. Each man thinks my practice is worth a different amount. I think about the tailoring I do of my physical self and digital self in order to satisfy these men and then consider the mental, intellectual, and emotional labor that is needed for a man to complete what I ask. The artworks are almost evidentiary objects of this labor. There is also humiliation in the drawing or painting as this is something they are not accustomed to. I often think when I meet them in a bar for the first time and pull out pens and paper that they believe it to be a pop psychology examination. In some irrational way, I suppose it is. They are all so desperate to be understood.

Have you ever had a submissive who is an art collector?

Yes, but he tried to patronize me. He would tell me that he collects Robert Crumb, Raymond Pettibon, stuff from David Zwirner. His taste in art is conventionally out there. At least by my standards.

He would patronize you about your art knowledge?

About my potential as an artist. But you know, it’s fine. Being patronized happens every day, doesn’t it?

What’s the best possible outcome from a relationship with a submissive that started out super right-wing, super misogynist, and has a fetish, obviously, for being dominated by women, but doesn’t understand that it is somehow related to his exterior life?

Introspection. True introspection. I don’t know if you can really change someone’s politics. The media certainly sensationalized these statements, but this was the plotline to my novella, Dining with Humpty Dumpty. Men come to me because they want to express something they hide in their everyday lives, so I see it as an opportunity to push them further. I believe women can change more easily than men, though. The male ego is a lot to keep up with.

What is an ideal relationship with a submissive like?

My favorite relationships are with the submissives who have a sense of humor, who are kind, and don’t feel sorry for themselves. The upper class of submissives seem to feel a deep sense of sorrow for themselves, and it’s very tiring. Sometimes they just end up feeling sorrier for themselves when they understand how they’ve dedicated their whole lives to performing this idea of success. This doesn’t necessarily lead them to actually changing anything. I also believe that the best outcome can be a unifying experience between myself and the submissive, one where we can enjoy society’s consideration of the tabooed relationship that we are experiencing together without shame. The weight of shame is a heaviness difficult to articulate and it is my job to nurture it for these men, which is another reason for me to test the power balance and reclaim my own work, so I am not caught in a nurturing, ultimately a maternal, role.

How are your submissives reacting to the artwork, if they see it? Do they come to the galleries?

Sometimes, and they like it. Wormy, for example, my all-time favorite, loves it. They all react differently. Most are aware of my art practice and often this intersects with their fantasy of me as a powerful woman. How much they are truly into this fantasy is what affects their reactions to the completed work. Most often, however, they don’t see real value in it because it is so averse to how they make money.

You have a new book coming out, correct?

It’s a zine. It’s a conversation between me and this really strange misogynist on a fetish website who started talking to me, saying he wants to interview me for his thesis. All of his questions were completely misogynistic and bizarre. He spoke using this faux-dated, academic prose. He called himself the Elysium Harvester, so the book’s titled Bints: A Conversation Between Mistress Rebecca and the Elysium Harvester. It’s called Bints because he referred to Simone de Beauvoir as a bint, which I think is an amazing word. The book is all about his project and my refusal to comply with it. He gets increasingly bizarre and strange, and then he keeps on coming back under different accounts on the fetish website—which, sadly, Trump’s FOSTA/SESTA laws are now working to delete. He then finds out my real name and that I’m less than half his age but teach for a master’s program without having done one and gets threatened. He was proposing to interview me for his master’s degree as a mature student. Now, he makes these different profiles on different social media networks to try to attack me. I’ve documented all the conversations and I’ve made it into a little booklet. I got a submissive to do the graphic design layout for me, the artwork, and to pay for it. All the proceeds are going to go to SWARM, which is a sex worker union.

In the end, does all of your literary and art work have socialist goals?

Yes, there are always socialist goals. It’s about men doing the labor and getting paid nothing other than sexual potential, the potential itself of having an erotic experience with me. It’s about always having these different laborers for me who are submissives. This is about a dissection of desire, between that one for sexual gratification and that one for monetary ideas of validation. I want to cut right through this tension and mold it into my own absurd vision. I am very aware that a huge part of what I do is selling my femininity. Under the patriarchy, this an unavoidable consequence of lived female reality. So, I’m exploiting it. This book is the first real practice of that. I’ve directly made submissives give to charities or spend in ways I deem more ethical, i.e. spending on friends’ businesses or purchasing things that I believe will educate them. But this book is completely sub-made. My labor as a dominatrix translates into the artwork. The pieces act as documents of a performative practice but also have physical values, representative of an emotional and therefore gendered labor and transaction. Obviously, it’s my intellectual labor, but it’s sub-made and the profit is going to a sex workers’ union. I want to start practicing with how I can use these men for the better by making my own libidinally-driven economy with them in the aim of creating more potential for women.

Natasha Stagg is the author of a novel, Surveys, and a forthcoming collection of stories, both published by Semiotext(e). Her work can also be found in the books, The Present in Drag by DIS (Berlin Biennale), Excellences and Perfections by Amalia Ulman (Prestel Publishing), You Had To Be There by Vanessa Place (Powerhouse Books), and Intersubjectivity Volume II by Lou Cantor and Katherine Rochester (Sternberg Press).